Minggu, 05 Agustus 2018

How Verbs Behave in the Exceptional Sequence

|

« on: October 13, 2016, 12:48:44 PM »

|

What follows is Chapter 52 of my book Give Your English the Winning Edge (Manila Times Publishing, 2009). I have decided to post it here in the Forum to answer the many lingering concerns and doubts—all understandably valid in the absence of specific guidance—of Forum member Michael Galario about the normal sequence-of-tenses rule in English. I am sure that other Forum members will find this essay instructive and revealing about one of the thorny and confusing aspects of reported (indirect) speech and inverted sentences.

In these troubled and troubling times when people’s utterances—whether expressed in private or aired through the broadcast, cellular, or print media—are increasingly being viewed with mutual suspicion, it would be useful to make a quick review of the grammar of reported speech. This would require a reacquaintance with how verbs behave in the normal sequence of tenses and in the so-called exceptional sequence. People should clearly understand this behavior of verbs so they can have a clearer, unbiased perception of the chronology and logic of fast-breaking events as they happen in time.

Reported speech or indirect speech is, of course, simply the kind of sentence someone makes when he or she reports what someone else has said. For instance, a company’s division manager might have told a news reporter these exact words: “I am resigning to join the competition.” In journalism, where the reporting verb is normally in the past tense, that statement takes this form in reported speech: “The division manager said he was resigning to join the competition.”

The operative verb in utterances obviously can take any tense depending on the speaker’s predisposition or intent. However, when an utterance takes the form of reported speech and the reporting verb is in the past tense, the operative verb of that utterance generally takes one step back from the present into the past: the present becomes past, the past usually stays in the past, the present perfect becomes past perfect, and the future becomes future conditional. This is the so-called normal sequence-of-tenses rule in English grammar.

Now let’s see how this rule applies when that division manager’s utterance is reported using the various tenses:

Present tense to past tense. Utterance: “I am resigning to join the competition.” Reported speech: “The division manager said he was resigning to join the competition.”

Past tense to past tense. Utterance: “I resigned to join the competition.” Reported speech: “The division manager said he resigned to join the competition.” (The past tense can usually be retained in reported speech when the intended act is carried out close to its announcement; if much earlier, the past perfect applies as shown below.

Present perfect to past perfect tense. Utterance: “I have resigned to join the competition.” Reported speech: “The division manager said he had resigned to join the competition.”

Future tense to future conditional tense. Utterance: “I will resign to join the competition.” Reported speech: “The division manager said he would resign to join the competition.”

Exceptional sequence. But there’s one very rare instance when the operative verb in reported speech doesn’t conform to this normal sequence of tenses. In the so-called exceptional sequence, which applies if the information being reported is permanently or always true, the operative verb in reported speech doesn’t take a tense backward but retains the present tense.

For instance, to prove a point, the division manager might have surprised his subordinates by saying an eternal verity like this: “A square has four sides of equal length.” This time, using the normal sequence-of-tenses rule to report that statement would be silly: “Our division manager said a square had four sides of equal length.” All squares will forever have four sides of equal length, so the exceptional sequence applies: “Our division manager said a square has four sides of equal length.”

But should the reported speech for habitual things also follow the exceptional sequence rule? Say, for instance, that right after declaring his intention to resign, that same division manager adds: “I am always loyal to the company I work for.” Would this reported speech for that utterance be correct: “He said he is always loyal to the company he works for”?

Definitely not. By his very words, the speaker has shown that loyalty is such a fickle thing, so the normal sequence-of-tenses rule applies to his reported speech: “He said he was always loyal to the company he worked for.”

In these troubled and troubling times when people’s utterances—whether expressed in private or aired through the broadcast, cellular, or print media—are increasingly being viewed with mutual suspicion, it would be useful to make a quick review of the grammar of reported speech. This would require a reacquaintance with how verbs behave in the normal sequence of tenses and in the so-called exceptional sequence. People should clearly understand this behavior of verbs so they can have a clearer, unbiased perception of the chronology and logic of fast-breaking events as they happen in time.

Reported speech or indirect speech is, of course, simply the kind of sentence someone makes when he or she reports what someone else has said. For instance, a company’s division manager might have told a news reporter these exact words: “I am resigning to join the competition.” In journalism, where the reporting verb is normally in the past tense, that statement takes this form in reported speech: “The division manager said he was resigning to join the competition.”

The operative verb in utterances obviously can take any tense depending on the speaker’s predisposition or intent. However, when an utterance takes the form of reported speech and the reporting verb is in the past tense, the operative verb of that utterance generally takes one step back from the present into the past: the present becomes past, the past usually stays in the past, the present perfect becomes past perfect, and the future becomes future conditional. This is the so-called normal sequence-of-tenses rule in English grammar.

Now let’s see how this rule applies when that division manager’s utterance is reported using the various tenses:

Present tense to past tense. Utterance: “I am resigning to join the competition.” Reported speech: “The division manager said he was resigning to join the competition.”

Past tense to past tense. Utterance: “I resigned to join the competition.” Reported speech: “The division manager said he resigned to join the competition.” (The past tense can usually be retained in reported speech when the intended act is carried out close to its announcement; if much earlier, the past perfect applies as shown below.

Present perfect to past perfect tense. Utterance: “I have resigned to join the competition.” Reported speech: “The division manager said he had resigned to join the competition.”

Future tense to future conditional tense. Utterance: “I will resign to join the competition.” Reported speech: “The division manager said he would resign to join the competition.”

Exceptional sequence. But there’s one very rare instance when the operative verb in reported speech doesn’t conform to this normal sequence of tenses. In the so-called exceptional sequence, which applies if the information being reported is permanently or always true, the operative verb in reported speech doesn’t take a tense backward but retains the present tense.

For instance, to prove a point, the division manager might have surprised his subordinates by saying an eternal verity like this: “A square has four sides of equal length.” This time, using the normal sequence-of-tenses rule to report that statement would be silly: “Our division manager said a square had four sides of equal length.” All squares will forever have four sides of equal length, so the exceptional sequence applies: “Our division manager said a square has four sides of equal length.”

But should the reported speech for habitual things also follow the exceptional sequence rule? Say, for instance, that right after declaring his intention to resign, that same division manager adds: “I am always loyal to the company I work for.” Would this reported speech for that utterance be correct: “He said he is always loyal to the company he works for”?

Definitely not. By his very words, the speaker has shown that loyalty is such a fickle thing, so the normal sequence-of-tenses rule applies to his reported speech: “He said he was always loyal to the company he worked for.”

Indignities in American Minor

Indignities in American Minor

By Jose A. Carillo This is much too unglamorous to admit, and my wife Leonor actually blanched when she read the first draft of this essay. But I told her firmly that it was a story I had to write once and for all as a cautionary tale for our times. Four years before September 11, 2001, while lined up at Los Angeles Customs for my flight back to Manila, U.S. agents had made me strip down to my underwear. It was not a particularly chilly autumn day in the West Coast, and America then was still the carefree blonde in a two-piece, traipsing barefoot on Long Beach, singing an innocent little ditty about freedom and clueless of the horrible outrage that was to befall her four years later. But even with the good heating at the airport I found myself shivering. I simply could not take the frisking and the progressive nakedness with grace and equanimity.  What a shame, I thought, to be put in the same class as the terrorists, mobsters, drug lords, and potbellied politicians who routinely deserved such searches! There I was, clothesless and listless in the City of the Angels, trying with some delicacy to shield with my hands as much of my crotch from the prying eyes that were all over me. But no matter how sophisticated I tried to look and how impeccable the English I used in my protestations, I was a practically naked alien under a host country’s sufferance, and short of begging, at that moment there wasn’t really much I could do to change that fact. The female agent also asked me to take off my shoes. She did it in probably much the same way that a fellow agent did it to a Filipino senator who, I read in the news just now, went through the same body search recently in San Francisco. I did not refuse nor even make a squeak, however. One reason was that I wasn’t a senator but a nobody. I would never know the pleasure of breezing through Customs without anybody laying as much as a hand on me, even if it was obvious that I carried contraband or a ton of plastic bomb on my belly. But what really took out much of the sting from the indignity was that I was not the only one targeted. And looking back, I realize now that it actually might have been my fault to be zeroed in along with the six who were behind me in the queue. Aside from wearing my old spring windbreaker that I regularly used for Decembers back home in Manila, I had the bad sense to hand-carry all the way from the East Coast a bulky, heavily padded green winter jacket lined with Teflon. I am actually of the lean sort, but I must have looked like a drug runner laden with cocaine whenever my bulk showed on their surveillance monitors. In any case, they asked me and the six others to step aside: a sixtyish woman in a wheelchair, an Oriental-looking gentleman in a very respectable-looking dark gray suit, and four or five Filipinos with their trademark huge shoulder bags and mountainous backpacks. The agents led us to a nearby inspection room, and in no time they had efficiently dismantled the wheelchair into a neat pile of tubes and nuts and bolts. They cautiously jiggled and peered inside each tube, but found nothing explosive or incendiary. Then the young, portly female agent, who looked every inch of Filipino parentage, frisked the old woman in the wheelchair, ever politely asking and helping her disengage the strap of her bra. Again there was nothing, not even a little vial of cocaine nor a lipstick case of crack for the effort. Then finally it was my turn. She started frisking me. In the best English that I could muster, I asked her: “Why have you chosen me for this? Do I look like a criminal?” And she replied in the best and most dispassionate Tagalog that she could muster: “Trabaho lang po. Natiyempuhan lang kayo.” (“Just doing my job, sir. You just happened to be it.”) Finding nothing on me, of course, she said: “Sori sir. Pasensiya na kayo.” (“I’m sorry for this. My apologies for doing it.”) She asked me to put my clothes back on, then waved the dignified-looking man to come forward. As he started to strip, the man tried his best to look nonchalant about the whole thing, but I noticed that his brow began to sweat and twitch a little. I suddenly had the inkling that the agents would not be disappointed this time. True enough, when the man took off his sando and was down to his briefs, there came into view several thick bundles of U.S. currency, securely bound with masking tape to the front, back, and sides of his torso. There must have several hundred thousands of dollars of the notes on him. “I’m sorry, sir,” the agent said with barely suppressed distaste, “you have attempted to take out currency beyond the $10,000-limit without declaring it, a violation of U.S. law.” She then asked all six of us to go, and began reading the man his Miranda rights. I may make light of the tough security measures that the U.S. now imposes on citizens and foreigners alike passing through its ports, but I do not really wish to trivialize what September 11 has done to the nation that we once knew as the Land of Milk and Honey. The fact is that September 11 has changed most of America’s icons and rules. And make no mistake about it now, because I say this in all practical seriousness: If you are going to San Francisco or LA or New York or Chicago, it will no longer be enough to wear flowers on your hair or make a “Peace!” sign with your fingers. You better be in your best form and best behavior. Give your paunch and toenails a good trim and don’t forget to wear clean socks. Have a nice haircut, and consider shaving off your prized mustache or goatee. Don’t bank on charm and diplomatic immunity. And remember, practice your English and watch your temper. Nothing will better qualify you for being asked to step aside the Customs queue in LA or San Francisco to be grilled or stripped than an atrocious or non-existent English or, much worse, a flare-up of a monumental ego. Sadly and forever, as the old refrain goes, everything is different now in America because of September 11. (2003) This essay, which first appeared in my English-usage column in The Manila Times and subsequently formed part of my book English Plain and Simple, is part of a collection of my personal essays from mid-2002 to date. I'll be running one of them in the Forum every Wednesday starting October 26, 2016. | ||||

| ||||

A World Without English

A World Without English

By Jose A. Carillo In the farming village where I grew up there was a man—a maker of homemade coconut oil—who did not believe in anything his mind could not grasp or which lay outside the life he knew. Let us call him Pedro de la Cruz. He was born at about the same time as my father in the early decades of the last century, but for some reason his schooling was cut short in the second grade, while my father went on to normal school in Manila to become a schoolteacher. Pedro thus could not understand, write, or speak English beyond the usual peremptory greetings like “Good morning!” or “Good afternoon!” Even these he affected to be beneath his dignity saying. In fact, he viewed with contempt people who spoke English in his presence; once they had left, he would spit on the ground and call them social climbers who surely would not make it to wherever it was they were going. “Mark my words,” he would say in the dialect, “they who think they are so good in a foreign tongue will soon come crashing to the ground!”  Pedro, along with his whole family, was intensely religious. Prayer colored his day as it did his wife Pilar, who was also hardly literate; his eldest son Gregorio, who was my classmate in grade school; Jacinto, the next born; and Teresita, their only daughter. Every morning when the parish church bell rang some two kilometers away, and again at Angelus, they would stop their hand-driven coconut press and pray all the Mysteries of the Holy Rosary. Sundays they would don their Sunday’s best for Holy Mass without fail, all five going to church on foot. Their religiosity, together with the almost unceasing oil-making in their small, hand-driven mill, was the central unifying force of their lives. Pedro was fiercely obstinate about the worldview that sustained this way of life. One time, back from Manila during a summer college break, I made the mistake of discussing Darwin’s Theory of Evolution with him. I explained that Darwin had determined that man might have sprung from the same prehistoric ancestral stock as that of the apes. This launched Pedro into a strangely eloquent diatribe against the false beliefs fostered by science and the infidels they produced. He gave me the disconcerting feeling that I was the biology teacher being prosecuted by William Jennings Bryan during the Scopes Monkey Trial, the only difference being that Clarence Darrow was nowhere around to defend me. And on matters like this, Pedro simply had to have the last word. You had to give up the argument because if you didn’t, it would go on past midnight in his hut, which in those days without electricity would be lit only by a flickering coconut-oil lamp. Pedro’s deep religiosity resulted in a frightening determinism. “Not a leaf will fall from the tree if God will not will it,” he would intone with fire in his eyes, “and that leaf will surely rise back to the twig if he wished it.” He also believed that God would surely provide for his family no matter what happened. For this reason, he did not think it necessary for any of his children to be educated beyond the level he had attained. In fact, he thought that every learning beyond this was simply a form of needless expense, a totally irrelevant enterprise that would only corrupt the way one ought to earn a living, grow into adulthood, raise a family, and end up in the grave like everybody else. The impact of this worldview was most profound in the case of Gregorio, who was in the same class with me from the second to the sixth grade. Gregorio’s talent in arithmetic was astonishing. He could add an eight-level array of ten-digit numbers in less than a minute, and could multiply a ten-digit number by another ten-digit number almost as fast. His grasp of English, unfortunately, was just above rudimentary. There had been no English-language reading materials in the de la Cruz household to stoke the fires of his otherwise brilliant mind, and the siblings could not or did not dare speak English with him. There was also no radio to stimulate his English comprehension; his father thought it a nuisance and a vexation to the spirit (TV was still a good 25 years away into the future). Had his English been at least as good as mine, which was by no means that good, I have no doubt that he would have been our class valedictorian. He could have gone on to high school and college and surely could have made something of himself, perhaps a mathematics or physics professor in a major university. But this was not be. Because Pedro did not send anyone of the siblings to high school and kept a life of penury, no money went out of the family bourse except those that went to food and the upkeep of their manual oil-making equipment. He kept his hut the thatched roof affair that it had always been, dismissing galvanized iron sheets as no good because they got so hot in summers; bought no motor vehicle, preferring to move on foot as always and to continue using a carabao-drawn cart to haul coconut and other cargo to his oil mill; and forced his family to live totally without entertainment and vice. This made the de la Cruz family outwardly prosperous and even enabled them to extend loans to the neighborhood in the form of coconut oil or petty cash. An emboldened Pedro could thus boast to the villagers that without even learning a word of English and without making his children take nonsense subjects in high school and college, his family was better off than most except the jueteng operator and the U.S. Navy pensionados in town. The neighborhood grew and flowed out; villagers moved to town, to the cities, to countries unknown and unheard off; houses big and small, built by money from overseas, sprouted all over. But Pedro’s hut stood unruffled and unchanged. After he and his wife passed away, the de la Cruz siblings continued to live in the same small, unfenced plot of land. They built satellite huts around their father’s, raised families, and set up their own hand-driven oil mills. But each had no dream or ambition beyond what their father had decreed. From each of the four hand-driven mills there would issue, day in and day out, the same peculiar sweetish odor of burnt coconut. Pedro’s legacy of a world without English would keep it that way until it had totally spent itself. This essay, which first appeared in my English-usage column in The Manila Times and subsequently formed part of my book English Plain and Simple, is part of a collection of my personal essays from mid-2002 to date. I’ll be posting one of them in the Forum every Wednesday from October 26, 2016 onwards. | ||||

| ||||

Rediscovering John Galsworthy

Rediscovering John Galsworthy

By Jose A. Carillo

Exactly twelve days after I was born in a small farming town in southeastern Philippines, the great director and actor Orson Welles broadcast on radio in Wisconsin a dramatic adaptation of John Galsworthy’s classic short-story, “The Apple Tree.” Of course there was no way that I could have known this at the time; I was only a malnourished infant in a country that had just come out of brutal enemy occupation. I only discovered the fact about this confluence of events four nights ago while surfing the modern-day marvel called the Web. I stumbled serendipitously on the complete script of Welles’ broadcast while looking for traces of the great love story that had so bewitched and given me so much pleasure one magical summer in the late 60s.

You must forgive me for what in every way looks like juvenile excitement over only an old story and an old English-language writer that modern anthologies seem to have even completely forgotten. But to me “The Apple Tree” was—and still is—the quintessential love story. The quiet tragedy between the London cosmopolite Frank Ashurst and the beautiful Welsh country lass Megan David, told with great empathy and narrative skill by a master of the English language, haunted me for years. To me it was just a happy accident that the story was written by a writer who was to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1932. Galsworthy was an English prose stylist so luminous in his language and so engaging in his storytelling that I gladly surrendered that summer and the next, reading practically the whole body of his novels and short fiction.

Take, as a first taste of Galsworthy, this passage from the opening lines of “The Apple Tree” as retold by Welles: “The familiar words of Hippolytus echoed in my mind: ‘The apple-tree, the singing, and the gold.’ The apple tree. And then, quite suddenly, I remembered. I’d been here before. Years before. I’d stood on this self-same hill. I knew the valley into which I looked. That ribbon of road and the old well behind. Life has moments of sheer beauty, of unbidden flying rapture that—they last no longer than the span of a cloud’s flight over the sun. I’d stumbled on just such a moment. In my own life, I’d stumbled on a buried memory of wild, sweet time.”

The English I am writing and you are reading now is, for the most part, what it is precisely because I had stumbled on “The Apple Tree” and Galsworthy and fell in love with both many years ago. It was in the public library of the British-Philippine Council, that time when it was still at old R. Hidalgo Street, in what is now largely Manila’s Muslim quarter in Quiapo. The story was part of a Galsworthy hardbound collection with russet cover simply entitled “Caravan.” I never got to own a personal copy of the book, but read and reread everything in it, so enchanted was I by Galsworthy’s narrative art, which was so far removed from the run of the English-language authors available to me at the time. But in the following years Galsworthy dropped out of sight from the shelves of bookstores. I looked far and wide to get a copy of “Caravan,” scouring every bookstore I could get myself into both here and in my travels, but could not find one. In time, distracted and enthused by English-language stylists with comparable if not greater facility with prose, I gave up my search for both the writer and the book.

But four nights ago, from the lens of more than half a century, there was Orson Welles in digital form talking to me about “The Apple Tree” and Galsworthy in his Mercury Theater dramatization of the story, sponsored intriguingly by then the leading American maker of beer. To the tune of the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, as indicated in the script, the great actor and director of “Citizen Kane” (which, it is probably worth mentioning, is considered the greatest film of all time) began: “Tonight, the Mercury brings you one of the loveliest of all love stories. It’s by John Galsworthy and it’s called ... ‘The Apple Tree’.” I almost fell off my computer swivel chair, so profound and delightful was my shock. The treasured gem that I had given up looking for after so many years was suddenly and literally in my fingertips again.

And so now I can relive again and again that unforgettable first encounter between Frank and Megan, as first imagined by the great Galsworthy and now retold by the digital Welles:

FRANK ASHURST (narrates): It was a girl. The wind blew her crude, little skirt against her legs and lifted her battered tam-o’-shanter. It was clear she was a country girl -- her shoes were split, her hands were rough and brown, and her hair waved untidily across her forehead. But her lashes were long and dark, and her gray eyes were a wonder: dewy, as if opened for the first time that day.

MEGAN: Hello.

ROBERT: Could you tell us if there’s a farm near here where we could spend the night? My friend’s getting pretty lame.

MEGAN: Well, there’s our farm, sir.

FRANK: Oh, could you put us up?

MEGAN: I’m sure my aunt would be glad to. If you like, I’ll show you the way.

The way that Megan showed to Frank was, in the small compass of “The Apple Tree,” a path that led not only to such great love and so much heartbreak, but also to some of the most compelling and beautiful lines of prose I have seen in English literature. I dare you now to tarry a little from your purely mundane pursuits to take that path. (circa 2002-2003)

This essay, which first appeared in my English-usage column in The Manila Times and subsequently formed part of my book English Plain and Simple, is part of a collection of my personal essays from mid-2002 to date. I’ll be posting one of them in Jose Carillo’s English Forum every Wednesday from October 26, 2016 onwards.

By Jose A. Carillo

Exactly twelve days after I was born in a small farming town in southeastern Philippines, the great director and actor Orson Welles broadcast on radio in Wisconsin a dramatic adaptation of John Galsworthy’s classic short-story, “The Apple Tree.” Of course there was no way that I could have known this at the time; I was only a malnourished infant in a country that had just come out of brutal enemy occupation. I only discovered the fact about this confluence of events four nights ago while surfing the modern-day marvel called the Web. I stumbled serendipitously on the complete script of Welles’ broadcast while looking for traces of the great love story that had so bewitched and given me so much pleasure one magical summer in the late 60s.

You must forgive me for what in every way looks like juvenile excitement over only an old story and an old English-language writer that modern anthologies seem to have even completely forgotten. But to me “The Apple Tree” was—and still is—the quintessential love story. The quiet tragedy between the London cosmopolite Frank Ashurst and the beautiful Welsh country lass Megan David, told with great empathy and narrative skill by a master of the English language, haunted me for years. To me it was just a happy accident that the story was written by a writer who was to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1932. Galsworthy was an English prose stylist so luminous in his language and so engaging in his storytelling that I gladly surrendered that summer and the next, reading practically the whole body of his novels and short fiction.

Take, as a first taste of Galsworthy, this passage from the opening lines of “The Apple Tree” as retold by Welles: “The familiar words of Hippolytus echoed in my mind: ‘The apple-tree, the singing, and the gold.’ The apple tree. And then, quite suddenly, I remembered. I’d been here before. Years before. I’d stood on this self-same hill. I knew the valley into which I looked. That ribbon of road and the old well behind. Life has moments of sheer beauty, of unbidden flying rapture that—they last no longer than the span of a cloud’s flight over the sun. I’d stumbled on just such a moment. In my own life, I’d stumbled on a buried memory of wild, sweet time.”

The English I am writing and you are reading now is, for the most part, what it is precisely because I had stumbled on “The Apple Tree” and Galsworthy and fell in love with both many years ago. It was in the public library of the British-Philippine Council, that time when it was still at old R. Hidalgo Street, in what is now largely Manila’s Muslim quarter in Quiapo. The story was part of a Galsworthy hardbound collection with russet cover simply entitled “Caravan.” I never got to own a personal copy of the book, but read and reread everything in it, so enchanted was I by Galsworthy’s narrative art, which was so far removed from the run of the English-language authors available to me at the time. But in the following years Galsworthy dropped out of sight from the shelves of bookstores. I looked far and wide to get a copy of “Caravan,” scouring every bookstore I could get myself into both here and in my travels, but could not find one. In time, distracted and enthused by English-language stylists with comparable if not greater facility with prose, I gave up my search for both the writer and the book.

But four nights ago, from the lens of more than half a century, there was Orson Welles in digital form talking to me about “The Apple Tree” and Galsworthy in his Mercury Theater dramatization of the story, sponsored intriguingly by then the leading American maker of beer. To the tune of the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, as indicated in the script, the great actor and director of “Citizen Kane” (which, it is probably worth mentioning, is considered the greatest film of all time) began: “Tonight, the Mercury brings you one of the loveliest of all love stories. It’s by John Galsworthy and it’s called ... ‘The Apple Tree’.” I almost fell off my computer swivel chair, so profound and delightful was my shock. The treasured gem that I had given up looking for after so many years was suddenly and literally in my fingertips again.

And so now I can relive again and again that unforgettable first encounter between Frank and Megan, as first imagined by the great Galsworthy and now retold by the digital Welles:

FRANK ASHURST (narrates): It was a girl. The wind blew her crude, little skirt against her legs and lifted her battered tam-o’-shanter. It was clear she was a country girl -- her shoes were split, her hands were rough and brown, and her hair waved untidily across her forehead. But her lashes were long and dark, and her gray eyes were a wonder: dewy, as if opened for the first time that day.

MEGAN: Hello.

ROBERT: Could you tell us if there’s a farm near here where we could spend the night? My friend’s getting pretty lame.

MEGAN: Well, there’s our farm, sir.

FRANK: Oh, could you put us up?

MEGAN: I’m sure my aunt would be glad to. If you like, I’ll show you the way.

The way that Megan showed to Frank was, in the small compass of “The Apple Tree,” a path that led not only to such great love and so much heartbreak, but also to some of the most compelling and beautiful lines of prose I have seen in English literature. I dare you now to tarry a little from your purely mundane pursuits to take that path. (circa 2002-2003)

This essay, which first appeared in my English-usage column in The Manila Times and subsequently formed part of my book English Plain and Simple, is part of a collection of my personal essays from mid-2002 to date. I’ll be posting one of them in Jose Carillo’s English Forum every Wednesday from October 26, 2016 onwards.

How I Discovered Gabriel García Márquez

How I Discovered Gabriel García Márquez

By Jose A. Carillo

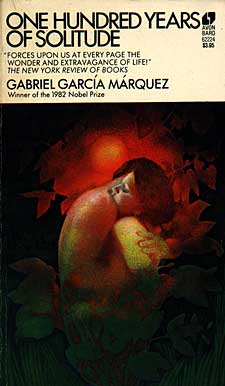

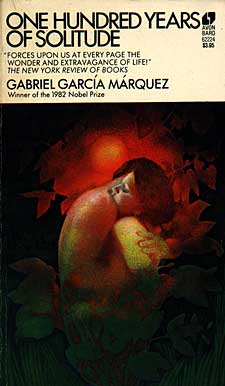

It is a very private story that I occasionally tell, but only to aspiring literary types, younger executives, and teenage bookworms who find time to ask me what is a good English-language book or novel to read. The story is about how, many years ago, I discovered Gabriel García Márquez in the romance section of a big bookstore at Claro M. Recto Avenue in Manila. It was shortly before or right after martial law had taken the life of the daily paper where I worked as a roving reporter, I cannot remember the exact date now. But there was Márquez, still a total stranger to me, in the Avon hardback edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude (Cien Años de Soledad in the original Spanish), enjoying in the same shelf the company of such rupture-and-heartbreak novelists as Emily Loring, Barbara Cartland, and Jacqueline Susann. No, García Márquez did not get there as an occasional stray, chucked absentmindedly or insensitively into the shelf by some browser. If memory serves me well, the book had been actually misclassified and miscatalogued in the same genre as the more popular company it was keeping when I found it.

The reason why it got there was probably serendipity of the most sublime order, but I think you can dismiss that thought as just me imagining the whole thing in chronological reverse. A more plausible reason was that it had the green and grainy cover art of a naked man and woman in passionate embrace, which I later thought was the publisher’s well-intentioned attempt to make the Buendia family’s otherwise unimaginable tragedies and grief more commercially acceptable. It was actually this somber study in solarized chiaroscuro that drew my eye to the book. When I began to leaf through it, however, furtively expecting some passages about women in the throes of illicit sex, I read something much more exciting, much more stimulating, and much more intriguing. “Many years later,” García Márquez began, “as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” A few passages later I was irretrievably sold to the book. I promptly paid for it, tearing the plastic wrapping no sooner had the sales clerk sealed it, and started to read as I trudged the sidewalk on my way to my apartment somewhere in the city.

When I had read the book twice or thrice and still couldn’t get over the thrill of the discovery, I excitedly recommended and lent it to a broadcast acquaintance at the old National Press Club. I can’t remember now who the borrower was, but he was one of those press club habitues who would dawdle over beer or gin tonic at the bar till somebody’s self-imposed midnight closing song-and-piano piece was over. What I do remember is that he never returned it to me. He assured me, however, that he had read it and enjoyed it so much that he could not resist lending it to someone—was it Carmen Guerrero-Nakpil or the late Renato Constantino?—who in turn lent it to someone who lent it to someone until finally the chain in the lending was lost. The last I heard from the original borrower was that the book had been passed on to an English Lit. professor at the University of the Philippines, where a few years later I was to learn that it had become mandatory reading in its English graduate school.

Being pathetically inept in Spanish, I could never really know what Castilian or Colombian idioms I missed in the English translation, but the English-language García Márquez in One Hundred Years of Solitude truly set my mind on fire. He lit in me a tiny flame at first, then a silent fire for language that burned even brighter with the passing of the years. He was not only robust and masterful in his prose but devastatingly penetrating in his insights about the flow and ebb of life in the archetypal South American town of Macondo. Not since I chanced upon a battered copy of The Leopard (Il Gatopardo in the original Italian) by the Italian writer Giuseppe di Lampedusa two years earlier, this time a real stray in a smaller bookstore nearby, had I seen such soaring yet quietly majestic writing. Here is García Márquez at his surreal best: “Fernanda felt a delicate wind of light pull the sheets out of her hands and open them up wide. Amaranta felt a mysterious trembling in the lace on her petticoats as she tried to grasp the sheet so that she would not fall down at the instant when Remedios the Beauty began to rise. Ursula, almost blind at the time, was the only person who was sufficiently calm to identity the nature of that determined wind and she left the sheets to the mercy of the light as she watched Remedios the Beauty waving goodbye in the midst of the sheets of the flapping sheets that rose up with her…” With prose like this I became a García Márquez pilgrim, re-reading One Hundred Years of Solitude countless times and devouring, like an adolescent glutton, practically all of his novels and short-story collections in the years that followed.

Many years later, in 1982, I was to discover in the morning papers that García Márquez had so deservedly won the Nobel Prize for literature. I was so happy for the new Nobel Laureate and for myself, and I no longer thought anymore of ever recovering that first copy of him that I had the pleasure of retrieving from the company where it obviously didn’t belong. In homage I went back to the bookstore where I first found García Márquez, quietly and almost reverently picking up a new Picador paperback edition of him. Its cover art was no longer the man and woman in the deathless embrace, but this time an image more faithful to the elemental truth of the book: the whole Buendia family in a portrait of domestic but elegiac simplicity, at one and at peace with the chickens and shrubs and flowers that gave them sustenance, awaiting the last of the one hundred years allotted to them on earth.

The book is mottled with age and yellow with paper acid now. Now and then I would lend it to a soul that is intrigued why I would keep such a forlorn book on my office desk, but only after tragicomically extracting an elaborate pledge that he or she would really read it and give it back to me no matter how long it took to finish it.

--------------

This essay originally appeared in the author’s “English Plain and Simple” column in The Manila Times in 2002 and subsequently became Chapter 40, Section 7 of his book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language. Copyright 2004 by Jose A. Carillo. Copyright 2008 by Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

By Jose A. Carillo

It is a very private story that I occasionally tell, but only to aspiring literary types, younger executives, and teenage bookworms who find time to ask me what is a good English-language book or novel to read. The story is about how, many years ago, I discovered Gabriel García Márquez in the romance section of a big bookstore at Claro M. Recto Avenue in Manila. It was shortly before or right after martial law had taken the life of the daily paper where I worked as a roving reporter, I cannot remember the exact date now. But there was Márquez, still a total stranger to me, in the Avon hardback edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude (Cien Años de Soledad in the original Spanish), enjoying in the same shelf the company of such rupture-and-heartbreak novelists as Emily Loring, Barbara Cartland, and Jacqueline Susann. No, García Márquez did not get there as an occasional stray, chucked absentmindedly or insensitively into the shelf by some browser. If memory serves me well, the book had been actually misclassified and miscatalogued in the same genre as the more popular company it was keeping when I found it.

The reason why it got there was probably serendipity of the most sublime order, but I think you can dismiss that thought as just me imagining the whole thing in chronological reverse. A more plausible reason was that it had the green and grainy cover art of a naked man and woman in passionate embrace, which I later thought was the publisher’s well-intentioned attempt to make the Buendia family’s otherwise unimaginable tragedies and grief more commercially acceptable. It was actually this somber study in solarized chiaroscuro that drew my eye to the book. When I began to leaf through it, however, furtively expecting some passages about women in the throes of illicit sex, I read something much more exciting, much more stimulating, and much more intriguing. “Many years later,” García Márquez began, “as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” A few passages later I was irretrievably sold to the book. I promptly paid for it, tearing the plastic wrapping no sooner had the sales clerk sealed it, and started to read as I trudged the sidewalk on my way to my apartment somewhere in the city.

When I had read the book twice or thrice and still couldn’t get over the thrill of the discovery, I excitedly recommended and lent it to a broadcast acquaintance at the old National Press Club. I can’t remember now who the borrower was, but he was one of those press club habitues who would dawdle over beer or gin tonic at the bar till somebody’s self-imposed midnight closing song-and-piano piece was over. What I do remember is that he never returned it to me. He assured me, however, that he had read it and enjoyed it so much that he could not resist lending it to someone—was it Carmen Guerrero-Nakpil or the late Renato Constantino?—who in turn lent it to someone who lent it to someone until finally the chain in the lending was lost. The last I heard from the original borrower was that the book had been passed on to an English Lit. professor at the University of the Philippines, where a few years later I was to learn that it had become mandatory reading in its English graduate school.

Being pathetically inept in Spanish, I could never really know what Castilian or Colombian idioms I missed in the English translation, but the English-language García Márquez in One Hundred Years of Solitude truly set my mind on fire. He lit in me a tiny flame at first, then a silent fire for language that burned even brighter with the passing of the years. He was not only robust and masterful in his prose but devastatingly penetrating in his insights about the flow and ebb of life in the archetypal South American town of Macondo. Not since I chanced upon a battered copy of The Leopard (Il Gatopardo in the original Italian) by the Italian writer Giuseppe di Lampedusa two years earlier, this time a real stray in a smaller bookstore nearby, had I seen such soaring yet quietly majestic writing. Here is García Márquez at his surreal best: “Fernanda felt a delicate wind of light pull the sheets out of her hands and open them up wide. Amaranta felt a mysterious trembling in the lace on her petticoats as she tried to grasp the sheet so that she would not fall down at the instant when Remedios the Beauty began to rise. Ursula, almost blind at the time, was the only person who was sufficiently calm to identity the nature of that determined wind and she left the sheets to the mercy of the light as she watched Remedios the Beauty waving goodbye in the midst of the sheets of the flapping sheets that rose up with her…” With prose like this I became a García Márquez pilgrim, re-reading One Hundred Years of Solitude countless times and devouring, like an adolescent glutton, practically all of his novels and short-story collections in the years that followed.

Many years later, in 1982, I was to discover in the morning papers that García Márquez had so deservedly won the Nobel Prize for literature. I was so happy for the new Nobel Laureate and for myself, and I no longer thought anymore of ever recovering that first copy of him that I had the pleasure of retrieving from the company where it obviously didn’t belong. In homage I went back to the bookstore where I first found García Márquez, quietly and almost reverently picking up a new Picador paperback edition of him. Its cover art was no longer the man and woman in the deathless embrace, but this time an image more faithful to the elemental truth of the book: the whole Buendia family in a portrait of domestic but elegiac simplicity, at one and at peace with the chickens and shrubs and flowers that gave them sustenance, awaiting the last of the one hundred years allotted to them on earth.

The book is mottled with age and yellow with paper acid now. Now and then I would lend it to a soul that is intrigued why I would keep such a forlorn book on my office desk, but only after tragicomically extracting an elaborate pledge that he or she would really read it and give it back to me no matter how long it took to finish it.

--------------

This essay originally appeared in the author’s “English Plain and Simple” column in The Manila Times in 2002 and subsequently became Chapter 40, Section 7 of his book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language. Copyright 2004 by Jose A. Carillo. Copyright 2008 by Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

The Evil That Ignorance and Incompetence Can Do

The Evil That Ignorance and Incompetence Can Do

By Jose A. Carillo

Many years ago, when I was in second year high, something happened that changed my family’s fortunes forever. We looked forward to a bountiful harvest that summer in our two-hectare citrus orchard in a farming town in the Bicol Region. After more than ten years of backbreaking nurture, the orchard’s more than 200 citrus trees had finally reached full fruition. They had already fruited four times during the previous two years, yielding fruits so luscious they attracted even wholesale buyers from faraway cities. This time the trees blossomed even more profusely, and my father expected a harvest at least double the previous one. A long-awaited prosperity was finally in sight for the family.

Due to unexpected rains in January of that year, however, a dense growth of weeds, cogon (a local reed), and creeping vines had enveloped the orchard. My father, at that time an elementary school head teacher, was terribly upset by this; if the undergrowths were left unchecked, the trees would choke and the harvest volume would drop. But farmhands were hard to find at the time; most were on extended summer-long rice harvesting sorties elsewhere in the province. Desperate, my father sent word through relatives and friends that he needed someone to clean up the orchard very quickly.

The day after, a man came to our house for the job. He was in his late 50s or early 60s, practically a stranger in our parts because he lived with his in-laws in a faraway village for most the year. He wasn’t the usual weather-beaten person who worked in farms. He arrived astride a strikingly clean carabao (water buffalo), without the usual flecks of dried-up mud that drew swarms of gnats and flies in their wake. He was so neat even in ordinary clothing, sporting a bolo with a handsomely crafted handle and an intricately carved scabbard. Although a man of very few words, he was prone to hyperbole, the way some unschooled people would try to show off that they are intelligent and worldly wise. In any case, he convinced my father that he could do the job on contract in four days flat. My father, deathly worried about his citrus harvest, readily accepted the man’s stiff quotation and gave him a hefty cash advance.

The man came back the following morning with two teenage farmhands in tow. I accompanied them to the orchard, which was about 150 meters away, hidden from view by a thick bamboo grove and a clump of trees. On arrival they promptly started hacking away at the undergrowth with their hoes and shovels, cutting deep into the soil, severing the surface roots of the citrus, and exposing earthworms all over the place. I remonstrated against this brutal weeding process, which would usually be done with long bolos, but the man simply laughed and said in the vernacular, “Don’t worry, son, there are more of those earthworms where they come from.” “Yes, but please cut only the grass and the vines and don’t dig deep into the ground,” I said. “Otherwise, you’ll be damaging the roots of the citrus.” “All right,” the man relented. “We’ll cut gentler and shallower, but tell your father that it will slow us down.”

The three made good progress. By the third day they had already cleared over three fourths of the orchard’s undergrowth, methodically piling up the cuttings outside the now-bare circular areas underneath the foliage of each citrus tree. In the summer heat the cuttings quickly dried up and turned brown and crisp, the sight of which made my father remark with elation that they would soon crumble, decay, and turn into natural fertilizer for the trees. My father was obviously delighted with his decision to hire the man, who had proved very efficient in his work.

Past three in the afternoon of the fourth day, the man and his three assistants came to our house and informed us that they had finished the job. We served them refreshments in appreciation, after which my father gladly handed the man the final payment—plus a generous tip. “Thank you,” was all the man said. As he and his assistants were leaving, however, he turned around and added: “By the way, it wasn’t part of the contract, but we thought of doing something extra to spare you the trouble. We burned the cut grass and vines to make the fruit orchard really clean. We set fire to the pile from all four corners of the orchard, so I think all of that unsightly debris should be gone by now. Check it out for yourself.”

Even now, many years later, I still can’t imagine by what perverse logic and reasoning anyone could have done it, but along with the cut grass and vines, the man had burned practically all of the citrus trees and our future to a crisp. (circa 2003)

This essay, which first appeared in my English-usage column in The Manila Times in 2003 and subsequently formed part of my book Give Your English the Winning Edge, is part of a collection of my personal essays from mid-2002 to date. I’ll be posting one of them in Jose Carillo’s English Forum every Wednesday from October 26, 2016 onwards.

Jumat, 03 Agustus 2018

The Germ of an Idea

The Germ of an Idea

By Jose A. Carillo How do you bring a practically dead river back to life? Do you tell the teeming occupants of its banks to please, please kindly dismantle their shanties and stop draining their wastes into its currents? Do you ask for loose change to save the river by deploying fancy carton deposit boxes in bank teller’s cages, drugstore counters, and supermarket checkouts? Do you write sense-of-loss letters to newspaper editors and hold rock concerts and sing paeans of how it was when, during the great Jose Rizal’s time, people could actually drink water from the river without risk of getting sick or dying from mercury poisoning or excess of E. coli? A few years back, I heard a story that said there was a better answer, and that one man had actually already discovered it. I was incredulous at first because the story was simply too good to be true, and because I heard it not from a fellow Filipino who could sympathize with this country’s dire and screaming need for self-regeneration. Instead I heard it from a South Korean heavy equipment distributor and motor shop executive, that morning while I waited for his mechanics to resuscitate my ailing 1992 Toyota Corolla. Having neither political motive nor hidden agenda (other than perhaps to brighten up the day for an increasingly impatient customer), the foreigner, whom we will fictitiously call Mr. Chung for this narrative, told the story with an unmistakable ring of truth. In the halting but clear English that some Korean businessmen finally manage after staying in the Philippines for a few years, Mr. Chung recalled a most intriguing day when he paid a visit to a town mayor that he was trying to interest in his heavy equipment. The mayor’s staff had told him over the phone that the mayor was greatly disposed towards approving his bid, which they said was much cheaper and better than all the bids they had received. The mayor wanted to finalize the deal with him right away, so could he please come over at once to see him? “Mr. Chung,” the Korean executive quoted the mayor as saying right after the usual introductions, “I will go directly to the point. When you prepared this bid for our garbage dump trucks, how much in overprice money did you put in it for us?” The Korean said he was so dumbfounded by the question that he could not speak for several minutes. He became dizzy from the thought that the overprice he had put in was too low, and that now he was reaping the bitter fruit of his stupid stinginess. But when the mayor repeated the question, a little more sternly this time, he realized he had to give an answer. With a catch in his throat he finally muttered: “It’s exactly 30 percent, Mr. Mayor.” To his surprise the mayor said without missing a beat, looking him straight in the eye: “I see. I see. All right, Mr. Chung, I want you to know that I do not allow and accept such add-ons in our contracts for this town. Here’s what I want you to do if you want us to do business with you: knock off that 30 percent from your quotation and send me the reduced one right away. I will have it approved and you can make the deliveries as soon as you can. Do you understand that?” “Yes, Mr. Mayor, if that’s what you want,” the Korean recalled having blurted in his daze, following it up hastily with the formalities of leaving. But as he was heading for the door he remembered having recovered enough sense to make this final pleasantry to the mayor: “Thank you so much again, Mr. Mayor. Is there anything my company can do for you in appreciation for giving us your business?” “Nothing really, thanks,” the Korean said the mayor replied. “But wait, tell me...I heard a great deal about your Olympic Park in Seoul. I remember somebody telling me that your government built it for the 1988 Olympic Games and that it’s simply beautiful. I am particularly interested in your Han River regatta course and your Mong-Chong moat. How your country restored that ancient artificial lake for the Olympics intrigues me! I also heard that you have the largest music fountain in Asia. Somebody told me the water goes 88 meters high, changes 1,400 times with the laser lights, and plays 140 different songs. And a world-class Olympic sculpture park, too! What great things your country had done in Korea in the name of sports and national pride, Mr. Chung!" “Yes, Mr. Mayor, our Olympic Park is as beautiful as you have heard,” the Korean recalled having said with a happy jolt in his heart, in the most fluent English that he could muster. “If you find time to visit Seoul I would be delighted to accompany you to those places myself. Autumn will be a particularly enchanting time for you and your environmental staff to come. Just give the date and I will be there to show you around.” “I will seriously think of going, Mr. Chung,” the mayor said. “Have a nice day!” Several months later, the Korean executive said, huge dredging equipment began cleaning up the putrid stretch of the river that runs through the mayor’s small town. The squatters that choked its banks completely disappeared. Within the year that stretch of river became clear and freely flowing again. As a finishing touch, a singing water fountain with laser lights started performing in midriver one night, and in the days that followed a sculpture park of farmers and water buffaloes and herons in concrete started to gaily assemble along its scrupulously clean and neat banks. (circa 2003) This essay, which first appeared in my English-usage column in The Manila Times in 2003 and subsequently formed part of my book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language, is part of a collection of my personal essays from mid-2002 to date. I’ll be posting one of them in Jose Carillo’s English Forum every Wednesday from October 26, 2016 onwards. | ||||

| ||||

The Lovely Clichés Worth Keeping

The Lovely Clichés Worth Keeping

By Jose A. Carillo

Our job as learners and users of the English language is to be discerning enough to know whether or not a catchy turn of phrase has already descended into the depths of cliché. This is not easy to do. It needs a lot of listening to English as spoken by its countless speakers all over the world. It requires reading a lot of English literature as written by modern and contemporary writers. In fact, there simply is no other way to be current with one’s English than to have a lifelong love affair with it.

Some clichés may be forgivable or even worth keeping, as with some truly memorable lines that have been recorded for posterity in verse or song, like “as time goes by,” “love is a many splendored thing,” and “splendor in the grass.” But there are cliché-like expressions that we should be merciless about. We should hunt them down and take no prisoners. They are the ones that, like legalese, try their best to browbeat us into unthinking followers. Deadly examples are the largely empty and meaningless terms that bureaucrats and aspiring bureaucrats use, such as “at this point in time” (now), “give consideration to” (consider), “it is the opinion of this office” (we believe), “with reference to” (concerning), “it is our duty to be cognizant of ” (we need to know), and “You are hereby advised that as of this date” (Today, you need to know). We all have to slog through them every time we deal with bureaucracy and corporate officialdom.

The thing is that in earlier times, what is often called “official prose” probably started as a gentler nudge or milder call to action: “Please do this” and “Kindly do that” and that sort of thing. But as bureaucracies and corporate organizations grew and became more complex, it became harder and harder to get people to comply. English had to be invented that had a coercive, punitive ring to it. There had to be no vulnerable human face; instead there could only be the big bureaucratic or corporate imprimatur, cold and imposing. And so was born the impersonal officious, official prose, or what is now called by some as “bureaucratese” or “corporatese.” It is the English that tells you to “obey or face the consequences.” It is a horrible legacy of our colonial times that organizations today have only begun to shrug off, not without shame and embarrassment, and only with half-baked results. A glance at a random stack of memos in many government or company offices studded with clichés will attest to this.

When, you might ask, does a respectable turn of phrase approach the threshold towards clichédom? “Bide one’s time,” “bring to mind,” “break the ice,” and “break fresh ground” look still secure enough from becoming clichés. They have not outlived their purpose yet. But “bite the bullet,” “bite the dust,” and “bite the hand that feeds you” have, I am afraid, all gone the way of the dead clichés. The atmospherics of the Old West that gave life to them simply are no longer around. “Burn one’s bridges behind” and “burn the candle at both ends” have concededly also become anachronisms, as with “sling one’s hook,” “by hook or by crook,” and “a stitch in time saves nine.” But I think that “break the news,” “break up with someone,” and “break it to me gently” will continue to stand the test of time “come what may.”

We can go on and on and get emotional about clichés, but we can afford this luxury only for a little while. We still have a lot of ground to cover about English and must put every minute to good use. So at this point, to check our progress, I want you to take a little English spot quiz. I call it the Helen Gurley Brown Test, in honor of the former editor of Cosmopolitan who, in her book The Writer’s Rules: The Power of Positive Prose, designed it as an exercise for identifying clichés. How many of them can you spot in her test passage below? I want you to honestly score yourselves as you do so.

Now that you have taken the test, I will let you in on a little conspiracy. From now on, you and I will be silent partners. We will be the final arbiters of what is cliché and what is not. But we will try to be as educated and knowledgeable about this as we go along. We will not impose any hard-and-fast rules because we know in our heart of hearts that it just won’t work. Hunting clichés should be a life-long avocation. Shooting a nasty one to death is pleasurable. But better still is to find a survivor and tweak it back to life, like making a deft, cliché-based feature headline in a newspaper or magazine. It is one of the little miracles of the English language. But do it only one at a time. Just on a thing or two. Hum it and make it sound good and haunting “like an old cliché,” as in that beautiful, half-forgotten song of a long time ago. (2002)

This essay first appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in The Manila Times in 2002 and subsequently appeared in Jose Carillo’s book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language. Copyright © 2004 by Jose A. Carillo. Copyright © 2004 by Manila Times Publishing. All rights reserved.

By Jose A. Carillo

Our job as learners and users of the English language is to be discerning enough to know whether or not a catchy turn of phrase has already descended into the depths of cliché. This is not easy to do. It needs a lot of listening to English as spoken by its countless speakers all over the world. It requires reading a lot of English literature as written by modern and contemporary writers. In fact, there simply is no other way to be current with one’s English than to have a lifelong love affair with it.

Some clichés may be forgivable or even worth keeping, as with some truly memorable lines that have been recorded for posterity in verse or song, like “as time goes by,” “love is a many splendored thing,” and “splendor in the grass.” But there are cliché-like expressions that we should be merciless about. We should hunt them down and take no prisoners. They are the ones that, like legalese, try their best to browbeat us into unthinking followers. Deadly examples are the largely empty and meaningless terms that bureaucrats and aspiring bureaucrats use, such as “at this point in time” (now), “give consideration to” (consider), “it is the opinion of this office” (we believe), “with reference to” (concerning), “it is our duty to be cognizant of ” (we need to know), and “You are hereby advised that as of this date” (Today, you need to know). We all have to slog through them every time we deal with bureaucracy and corporate officialdom.

The thing is that in earlier times, what is often called “official prose” probably started as a gentler nudge or milder call to action: “Please do this” and “Kindly do that” and that sort of thing. But as bureaucracies and corporate organizations grew and became more complex, it became harder and harder to get people to comply. English had to be invented that had a coercive, punitive ring to it. There had to be no vulnerable human face; instead there could only be the big bureaucratic or corporate imprimatur, cold and imposing. And so was born the impersonal officious, official prose, or what is now called by some as “bureaucratese” or “corporatese.” It is the English that tells you to “obey or face the consequences.” It is a horrible legacy of our colonial times that organizations today have only begun to shrug off, not without shame and embarrassment, and only with half-baked results. A glance at a random stack of memos in many government or company offices studded with clichés will attest to this.

When, you might ask, does a respectable turn of phrase approach the threshold towards clichédom? “Bide one’s time,” “bring to mind,” “break the ice,” and “break fresh ground” look still secure enough from becoming clichés. They have not outlived their purpose yet. But “bite the bullet,” “bite the dust,” and “bite the hand that feeds you” have, I am afraid, all gone the way of the dead clichés. The atmospherics of the Old West that gave life to them simply are no longer around. “Burn one’s bridges behind” and “burn the candle at both ends” have concededly also become anachronisms, as with “sling one’s hook,” “by hook or by crook,” and “a stitch in time saves nine.” But I think that “break the news,” “break up with someone,” and “break it to me gently” will continue to stand the test of time “come what may.”

We can go on and on and get emotional about clichés, but we can afford this luxury only for a little while. We still have a lot of ground to cover about English and must put every minute to good use. So at this point, to check our progress, I want you to take a little English spot quiz. I call it the Helen Gurley Brown Test, in honor of the former editor of Cosmopolitan who, in her book The Writer’s Rules: The Power of Positive Prose, designed it as an exercise for identifying clichés. How many of them can you spot in her test passage below? I want you to honestly score yourselves as you do so.

Quote

“Mary is known for giving as good as she gets. When Steve, trying to get her goat, told her she was ugly as sin, she was all over him like a tent. Who did he think he was, God’s gift to women? Not on your life, thought Mary. She could spot a sitting duck when she saw one and, in this case, Steve stuck out like a sore thumb. She went after him tooth and nail, calling him every name in the book, until he finally cried uncle and slunk away with his tail between his legs, a sadder and wiser man who learned his lesson the hard way.”

Now that you have taken the test, I will let you in on a little conspiracy. From now on, you and I will be silent partners. We will be the final arbiters of what is cliché and what is not. But we will try to be as educated and knowledgeable about this as we go along. We will not impose any hard-and-fast rules because we know in our heart of hearts that it just won’t work. Hunting clichés should be a life-long avocation. Shooting a nasty one to death is pleasurable. But better still is to find a survivor and tweak it back to life, like making a deft, cliché-based feature headline in a newspaper or magazine. It is one of the little miracles of the English language. But do it only one at a time. Just on a thing or two. Hum it and make it sound good and haunting “like an old cliché,” as in that beautiful, half-forgotten song of a long time ago. (2002)

This essay first appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in The Manila Times in 2002 and subsequently appeared in Jose Carillo’s book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language. Copyright © 2004 by Jose A. Carillo. Copyright © 2004 by Manila Times Publishing. All rights reserved.

Things My English Teacher Never Taught Me

Things My English Teacher Never Taught Me

By Jose A. Carillo

Through all these years, I thought I had already acquired enough proficiency in English that I can afford to be smug about it. Oh, yes, I can spin write-ups of the sort that the English literary greats had disdainfully termed “entertainments” to describe their lesser works, and can put polish to other people’s writings and speeches so that they are not entirely grammatical or rhetorical embarrassments. As friends would coarsely say in the vernacular when they have had a beer or gin tonic too many, by fiddling too much with English I seem to have acquired the knack to bounce it off effortlessly against the wall or to twirl it around my fingers. But the more I think about it, the more I am convinced that it’s really no big deal. Jai alai and basketball players can do much better than that with a Voit or Molten or a wicker pelota. So much so that just a few days ago, dejected over a major grammar lapse that gave me and my staff editors a slip, I declared to them, not entirely in jest, that if I won the lotto that very day, I would give up editing altogether and get into paleontology, like what the legendary explorer Roy Chapman Andrews had done in the 1920s, the anthropologist Loren Eiseley in the 1940s, or the paleontologist Stephen J. Gould in the past three decades or two.

Misty eyed I told my staff that I would promptly fly to Tanzania and importune Richard Leakey at his camp in Olduvai Gorge to take me in as an understudy. I would gladly volunteer my services to look for the definitive first human skull that had so far eluded his and his parents’ lifelong search as well as that of Andrews’ before them. That should nicely put some zing to a life that had been largely devoted to straightening out grammar, syntax, and logic in errant prose. In my waning years, I said, I could cap my new career by writing books about my adventures and possible discoveries in the desert wastes, like what Andrews, Eiseley, and Gould had done with admirable success.

Perhaps I should tell you a little bit about these three gentlemen for you to feel at least some sympathy for my wayward enthusiasms. Andrews it was who, searching in the Gobi Desert in southern Mongolia for the prehistoric human ancestor, found instead the skeleton of a small theropod dinosaur that had lived more than 100,000,000 years ago. That momentous find created a fascinating enigma about nature and the mother instinct that was to be solved only many decades later. But the adventures of Andrews during his widely publicized expeditions, recounted in his books On the Trail of Ancient Man and All About Dinosaurs, would inspire the fictional Indiana Jones that Steven Spielberg made a lot of money from in his blockbuster Raiders of the Lost Ark and its similarly successful sequels. Eiseley, of course, is my hands-down favorite English-language essayist; an evolutionary biologist, he wrote hauntingly beautiful meditations on man and dinosaurs in The Immense Journey, Darwin’s Century, and in his other essays and books. And Gould—all ten books by this outspoken Harvard professor, including Bully for Brontosaurus and The Panda’s Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History, that lay fallow in the home library of a brother-in-law dying of leukemia in the same plains in North America where dinosaurs once ruled like kings—became my emotional anchor as I watched the patient’s life ebb away in a blue haze that devastating autumn five years ago.

But now, going deeper into English grammar to do research on prepositional idioms and prepositional phrases for my column, I find a universe of English so totally new to me that I am beginning to change my mind again about my paleontologic dreams. In the quiet rush of my largely uneventful life in journalism and communication, I had only heard sound bites or seen snatches of this universe. It was a universe that my English teachers had only vaguely hinted at, so engrossed were they in their own rush to, say, get foreign fellowships or to earn a law degree to become a judge in some backwater town. It was the very same universe of Demosthenes the stuttering Greek, who, before becoming the greatest orator the world had ever known, would fill his mouth with pebbles and, racing with himself in Athens, attempt oratory at the top of his voice to cure his speech impediment. Today, his heroic efforts to fathom the wellsprings of words, along with his relentless pursuit of compelling writing and speech, have grown into the multifaceted universe of English linguistics and rhetoric. How I would have devoted my life to them had I discovered early enough their depth and breadth as intellectual disciplines!

In high school, my creative writing teacher taught me that there were 18 figures of speech, from alliteration and allusion down in the alpha list to the hyperbole, metaphor, metonymy, oxymoron, simile, and synecdoche. Now, I find to my great surprise that the ancient Greeks had in fact meticulously identified and catalogued no less than 80 of them—what they called the “flowers of rhetoric”—in much the same way that the Swedish Carolus Linnaeus had made sense of life’s diversity by giving each living thing a scientific name, and in much the same way that the Russian Dmitri Mendeleyev had classified the known basic substances and divined the existence of many others by painstakingly coming up with the periodic table of the elements. The pragmatics list of the ancient Greeks, or their choices of words and phrases to fit every conceivable speech or social situation, covered not only the 18 that I knew but also an astounding wealth of other figures of speech, like the agnomination, litote, ploce, preterition, polysendeton, similitude, syllepsis, and zeugma. It was this very same art and passion that the Greeks lavished on their language that not only gave fire to the timeless orations of Demosthenes but, for the most part, shaped both English and civilization as we know them today.

So now, just when I am about to sit back and take it easy with the thought that I have been there, done this, done that, I find that I have barely scratched the surface of the English that I was getting too familiar with to actually dream of trading it off with paleontology. (circa 2002)

This essay first appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in The Manila Times in 2002 and subsequently appeared in Jose Carillo’s book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language. Copyright © 2004 by Jose A. Carillo. Copyright © 2004 by Manila Times Publishing. All rights reserved.

By Jose A. Carillo

Through all these years, I thought I had already acquired enough proficiency in English that I can afford to be smug about it. Oh, yes, I can spin write-ups of the sort that the English literary greats had disdainfully termed “entertainments” to describe their lesser works, and can put polish to other people’s writings and speeches so that they are not entirely grammatical or rhetorical embarrassments. As friends would coarsely say in the vernacular when they have had a beer or gin tonic too many, by fiddling too much with English I seem to have acquired the knack to bounce it off effortlessly against the wall or to twirl it around my fingers. But the more I think about it, the more I am convinced that it’s really no big deal. Jai alai and basketball players can do much better than that with a Voit or Molten or a wicker pelota. So much so that just a few days ago, dejected over a major grammar lapse that gave me and my staff editors a slip, I declared to them, not entirely in jest, that if I won the lotto that very day, I would give up editing altogether and get into paleontology, like what the legendary explorer Roy Chapman Andrews had done in the 1920s, the anthropologist Loren Eiseley in the 1940s, or the paleontologist Stephen J. Gould in the past three decades or two.

Misty eyed I told my staff that I would promptly fly to Tanzania and importune Richard Leakey at his camp in Olduvai Gorge to take me in as an understudy. I would gladly volunteer my services to look for the definitive first human skull that had so far eluded his and his parents’ lifelong search as well as that of Andrews’ before them. That should nicely put some zing to a life that had been largely devoted to straightening out grammar, syntax, and logic in errant prose. In my waning years, I said, I could cap my new career by writing books about my adventures and possible discoveries in the desert wastes, like what Andrews, Eiseley, and Gould had done with admirable success.

Perhaps I should tell you a little bit about these three gentlemen for you to feel at least some sympathy for my wayward enthusiasms. Andrews it was who, searching in the Gobi Desert in southern Mongolia for the prehistoric human ancestor, found instead the skeleton of a small theropod dinosaur that had lived more than 100,000,000 years ago. That momentous find created a fascinating enigma about nature and the mother instinct that was to be solved only many decades later. But the adventures of Andrews during his widely publicized expeditions, recounted in his books On the Trail of Ancient Man and All About Dinosaurs, would inspire the fictional Indiana Jones that Steven Spielberg made a lot of money from in his blockbuster Raiders of the Lost Ark and its similarly successful sequels. Eiseley, of course, is my hands-down favorite English-language essayist; an evolutionary biologist, he wrote hauntingly beautiful meditations on man and dinosaurs in The Immense Journey, Darwin’s Century, and in his other essays and books. And Gould—all ten books by this outspoken Harvard professor, including Bully for Brontosaurus and The Panda’s Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History, that lay fallow in the home library of a brother-in-law dying of leukemia in the same plains in North America where dinosaurs once ruled like kings—became my emotional anchor as I watched the patient’s life ebb away in a blue haze that devastating autumn five years ago.